“You accepted me way too fast!”

This is what Tim Robinson’s character, Craig says to Paul Rudd’s character, Austin after Austin gives him the bad news that he doesn’t want to hang out with him. It was a phrase that kept dinging in my head when I was watching the movie “Friendship.” A maximalist comedy that takes the sensibilities of the sketches of “I Think You Should Leave” with a film making that skews more A24 drama. The movie is about Craig meeting Austin and Craig tripping over himself to be friends with him. And through that journey completely unraveling his life.

I watched this movie and yes I think it’s funny. Its the main thing. Tim Robinson is nothing but a master of the absurd and Craig is absurd, there’s some gags in there that are laugh out loud ridiculous. However the setting is realistic, the characters are realistic even though they may not act that way, and maybe it’s just me, but this movie outside of the idea that it wants you to laugh a lot, also asks you to take it seriously. So that’s what I’m going to do.

Most of the critical reviews of this movie talk more about the comedy aspect of it, very little of them talk about the actual theme of this movie, that male friendship, especially as an adult, is a tiring and exhausting and possibly crazy making experience. And since this is a substack about masculinity, let’s just go full out. Let’s talk about how cringe male friendship can be and why this movie “Friendship” is a great example of it.

Why this movie and why Tim Robinson?

Tim Robinson’s sketch show “I Think You Should Leave” is a masterclass on weirdness. A lot of Robinson’s sketches involves taking a situation that may seem normal and have a chaotic person (usually played by himself) enter the situation who will say or do the thing that you wish they didn’t do.

For example, it will be Tim trying to push on the pull door because he’s embarrassed to be wrong. It will be Tim playing a stupid video game on the work computer as the others are having a serious conversation, and the game becoming weirder as it goes on. It will be an elderly professor stealing food from his students. It will be Tim wanting to wear a stupid hat, and how that shows up in an unrelated court trial. A lot of the sketches stretch a normal social scenerio to it’s furthest limit, to a point where it can’t possibly get worse, and then they end. That’s how most of them go. But sometimes, they will reveal the heart of what I think Tim Robinson goes after. ”Ghost Tour” is a great example of this.

The premise is simple, Tim goes to an adult ghost tour which the host says that the guests are allowed to swear since it’s an adult tour. Tim, of course, takes that invitation to a point where it makes everyone uncomfortable and gets kicked out. However at the end of this skit, his mom picks him up he confesses to her that he didn’t make any friends.

Some of Tim’s skits end in this meloncholie way. It’s the heart in the middle of the chaos. It’s the characters admitting that they are insecure, or that they lack confidence, or they lack competence to live in the social world.

This lack of competence I believe is hidden at the heart of “Friendship” and I believe it’s the message. The tagline of this movie is a hint to that, and one that I want to explore thought this movie, a message that a lot of men (and maybe a lot of society) believe “Men shouldn’t Have Friends”

Friendship is Cringe

*this may contain spoilers for the movie ‘Friendship’, be warned*

Jamaal Burkmar, a writer and, where I found him, a TikTokker, says the phrase “Form Affects Results” in relation to how males usually relate to one another. Meaning that we were socialized to relate on a side by side setting. That both males before we could bond would have to do something in order to connect, that may be playing sports, or working on a project together, or fighting a battle together, or playing video games together. Generally doing something together would create a sense of comradery.

This is the form that most males encounter during their youth. There’s a bit of nature/nurture thing going on, because genuinely I don’t know where it comes from. I have seen young boys that are in pre-school that interact in this way, and that may come from their parents and how they were nurtured. But I also have seen this from boys who have been nurtured in ways to be more relational.

However one thing I do know about humans is that we have a pretty flexible brain that continues to learn until the day we die. And that it doesn’t have to be this way. If we believe that the foundation of male friendship comes from this side by side interaction, then the foundation becomes pretty weak pretty quickly.

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

What Jamaal says is that males are not accustomed to learning more about their male friends and the foundation of friendship is so fraught that for example, the breaking down of that activity that was shared, will result in the loss of that friendship. If someone outgrows the video game, if the project is complete, if the war is over, then all what happens is you’re stuck with another person and you have no idea on how to relate to that person. The result is loneliness.

Form affects results.

In “Friendship” you see this play out right at the start. The movie does a good job setting up Craig to be a man who is helping his wife who is battling cancer and his only son who is just being a teenager. He tries his best to be supportive but also has his own frame of view.

His wife, played by Kate Mara, is dealing with her own struggles, and Craig finds himself isolated even within his own family unit. His wife mentions that the only thing he does is stay in his couch the whole night after he gets back from his soul crushing job (an app developer that wants to create more addicting apps, a funny nod to the addiction Craig goes through).

When Craig meets Paul Rudd’s Austin, a cool weatherman on TV who just moved into the neighbourhood. It’s through Austin’s nonchalance that they even interact. Their meet cute is just generated through Austin’s coolness which Craig is attracted to, but not overly won over in the beginning. And at the start you can see that Austin and Craig really don’t click together, but this superficially is really not a problem, this is how most people meet honestly. This is not the issue.

The problem lies afterwards. The social incompetence that Craig has been operating from is a playbook that doesn't exist for adult male friendship. Austin represents the other side of this coin—a man who has learned to keep others at arm's length by performing coolness. And both of these styles of performative masculinity clash in ways that are hilarious, and chaotic. It’s a real neat trick to play this as a comedy, but there’s a lot of truth in this.

The Austin Problem: Coolness as Armour

Austin's character arc reveals another crucial aspect of adult male friendship: the performance of coolness as a defense mechanism. Throughout the film, Austin maintains a careful distance, presenting himself as effortlessly cool while Craig desperately tries to match that energy. But Austin's coolness isn't authentic confidence—it's a learned behavior designed to avoid the vulnerability that real friendship requires. It’s lack of sincerity. It’s trying to create depth where there’s only a shallow pond. And Craig who doesn’t know any better, buys this hook line and sinker.

When Austin initially accepts Craig's he's not being genuine; he's being polite. This is what makes Craig's eventual realization—"You accepted me way too fast!"—so devastating and insightful. Craig recognizes that Austin never actually wanted to be his friend, but was too socially conditioned to say no directly. And Craig gave his full self to Austin and Austin only shunted him away after a truly awkward hang out, a hang out (where they started to play fight) that showed a bit of weird macho male socialization.

This reflects a broader problem in male socialization: we're taught to be pleasant and agreeable in the moment while avoiding the honest communication that real relationships require. And the way we want to play, is through competition.

The Sincerity Trap

Craig's sincerity—his desperate, unfiltered need for connection—becomes toxic because it's unhampered by social awareness or respect for boundaries. Meanwhile, Austin's insincerity protects him from vulnerability but also prevents genuine connection.

This creates what we might call the "sincerity trap" of male friendship: be too genuine about your need for connection, and you become Craig. Overwhelming, desperate, lacking the skills to maneuver these social boundaries or even to talk about them.

On the other side, be too guarded, and you become Austin, emotionally unavailable, insecure, and not the cool guy that you want to be. You will, as Austin does, be found out. The film suggests there's no easy middle ground, which is why male friendship feels so precarious.

The Loneliness Epidemic

"Friendship" arrives at a time when male loneliness has reached maximum discourse. We have talked about this for ages, but I think it’s something that males have dealt with for centuries.

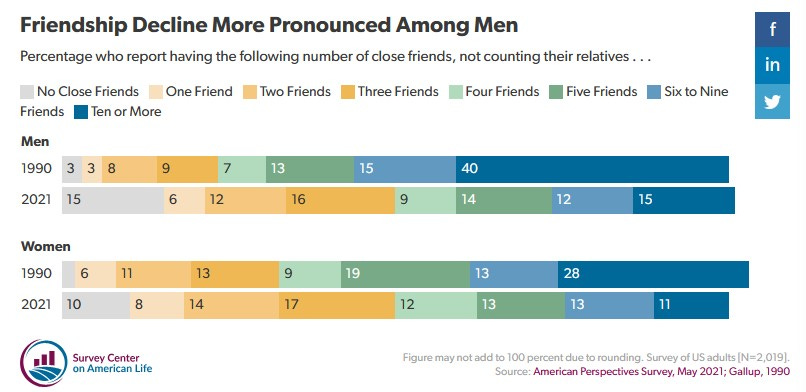

Studies consistently show that men report fewer close friendships than women, and that these friendships tend to be less emotionally intimate.

The film exaggerates this reality to absurd proportions, but the underlying truth remains: many men are starving for genuine connection while simultaneously lacking the tools to create and maintain it.

Craig's unraveling throughout “Friendship” represents the extreme end of this loneliness. He's so desperate for male companionship that he's willing to etry to copy something he doesnt have, coolness. The failing that, he spirals, the lesson he learns at the end is “we need rules!”

Form affects results. The foundation of male friendship was not there, and therefore the rules were never taught.

It's comedy through horror, showing us what happens when the need for friendship becomes pathological. However when you see this play out in real life, it’s cringy! It’s one person trying to act cool, while the other person not knowing what to do or what to say. Combine that with internalized homophobia and you have a recipe for awkwardness that ends up with the phrase “no homo!” as part of the male lexicon.

Beyond the Comedy

While "Friendship" operates as an absurdist comedy, its emotional core speaks to real struggles many men face. The film asks uncomfortable questions: What happens when traditional forms of male bonding (sports, work, shared activities) aren't enough? How do you form friendships as an adult when you lack the natural contexts that facilitated childhood connections? And perhaps most importantly: How do you express need without becoming needy?

Truth be told, I don’t have an answer for this. There is no magic bullet here. I know I’m not good at this, I have had male friends tell me that they are not good at this either. I have had many awkward things happen between male friends through the guise of trying to be friendly. And it’s awful, always. It’s not like all males are like this, there’s some that this social dance is very easy. I do know that I can’t be like Craig, but do people know that they can’t also be like Austin either? Tricky stuff.

The phrase "You accepted me way too fast!" becomes the key to understanding the entire film because it reveals the fundamental dishonesty that often underlies male social interaction. We say yes when we mean no, we perform interest when we feel indifference, and we avoid the direct communication that might actually lead to genuine connection.

Craig's realization is both an accusation and a confession. He's calling out Austin for his insincerity, but he's also acknowledging his own role in accepting superficial connection rather than demanding genuine interest. It's a moment of painful clarity that cuts through all the performative nonsense that has defined their relationship.

The Impossible Task

"Friendship" ultimately suggests that male friendship in its current form might be an impossible task. We're socialized in ways that make genuine connection difficult, we lack models for healthy adult male friendship, and we're often too proud or scared to admit our need for companionship.

But perhaps that's the point. By pushing these dynamics to their absurd extreme, Tim Robinson forces us to confront the ways that traditional masculinity fails men. And we as humans have ways to change that. We have the capacity to be different.

The film is funny because it's true, and it's disturbing because it reveals how broken our approaches to male connection really are. Or maybe you like it because you’re just a huge Tim Robinson fan, whatever. Why have a substack if I can’t take these things to the extreme.

“Friendship” offers a mirror. In Craig's desperate neediness and Austin's protective coolness, many men will see themselves. And maybe that recognition is the first step toward building something better—friendships based on genuine interest rather than social obligation, honest communication rather than performed coolness, and mutual vulnerability rather than competitive posturing.

In the end, "Friendship" is a comedy about the absence of friendship, a film about connection that reveals our profound disconnection. The fact that we can laugh at Craig's desperation doesn't make it less real; it makes it more urgent.

The tagline might as well be: "Men shouldn't have friends—but they desperately need them." And until we figure out how to bridge that gap, we'll keep getting movies like "Friendship"—brilliant, uncomfortable mirrors reflecting our collective failure to connect.